10 years in the life of a Jewish girl in rural Alsace. (1913-1923)

This article was inspired by three slightly dog-eared exercise books, lined pages stitched to handsome black covers proudly bearing the name and address of the INSTITUTION DE Mmes ARON & WEIL, RUE EMILE GALLE, NANCY in gold letters. Now a little faded, these three exercise books had been lovingly kept for years between the sheets in a linen cupboard. They had been written during the school year 1913-14 by Lucy Salomon. At the age of fourteen, she had been a boarder at this Pensionnat (boarding school) for Jewish girls. Together with personal testimonies, they reveal a great deal of the ethos of that institution.

Though 122 years had elapsed since the emancipation of the Jews of France in the wake of the Revolution, an analysis of the content of the exercise books clearly shows the characteristic attitude French Jews displayed towards France from 1791 date of the emancipation, until the Second World War. They saw themselves as Français et Israelites (French and Jewish). In accordance with that most important document of the Revolution, the Declaration des Droits de l'Homme (Declaration of Human Rights), the Jews of France had been granted freedom and equality. For the first time they were libres et egaux (free and equal). No longer could they be discriminated against; they were French citizens sharing equally the civic rights and duties of all French citizens. A great wave of gratitude towards France filled the hearts of French Jews. They wanted to be French, to feel French, to identify with their fellow French citizens, to espouse their causes, to join in their undertakings. They wanted to retain their Jewishness but this Jewishness had to bear the stamp of Frenchness. To give expression to this combined identity they called themselves Israelites Français and not Juifs Français thus eliminating the notion of foreignness the word Juif implied.

The prevailing spirit of the Enlightenment in Europe in the 18th century and that of the Haskalah or Jewish Enlightenment encouraged new thinking. Its call for secular education, its more rational approach to Jewish matters had freed the Jews from physical and mental ghettoes. It had found favour with the Consistoire Central de Paris (Central Consistory), head of the consistorial system of regional administrations for Jewish affairs instituted by Napoleon at the end of The Great Sanhedrin. By 1913-14, date of our exercise books the teachers at the Institution Aron et Weil were a true product of the Emancipation and of the Haskalah. They naturally adopted these philosophies in their teaching.

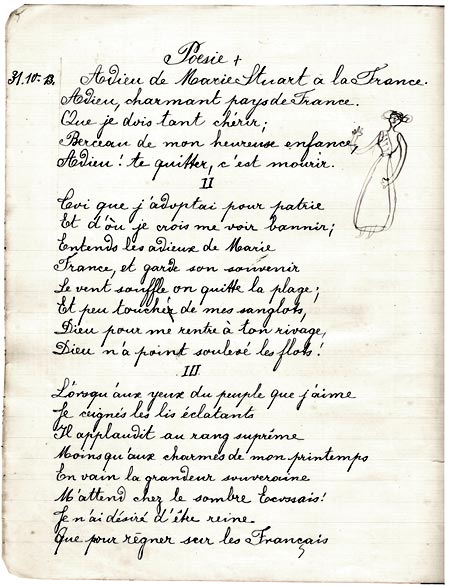

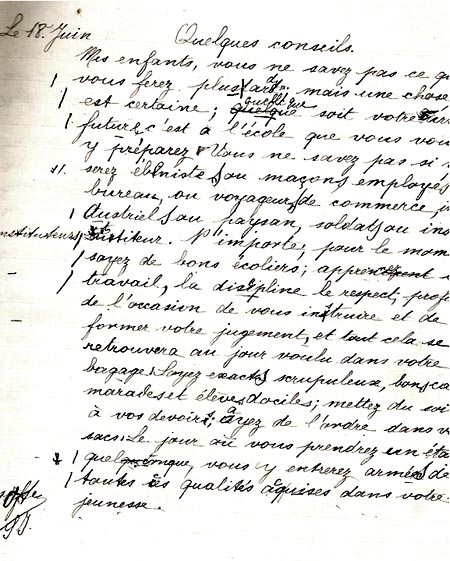

In one of the exercise books Lucy copied down poetry, in another she wrote compositions and in the third the daily dictées (dictations). The teaching of French occupied a predominant place in the curriculum as most of the girls came to the Institution primarily to improve their knowledge of the French language.

|

The conscientious marking of the students work, the careful planning of compositions, the comprehension exercises related to most dictées bear witness to the high professional standard of the teachers. Reading aloud and the recitation of memorised French texts provided oral practice. Names of authors are not always provided but there are passages attributed to Sully Prudhomme, Victor Hugo, Andre Chenier, Tolstoy, Francois Coppée, Florian, Jacques Normands, Erckmann Chatrian and other well-known writers and poets.

It is the content of the texts as well as the composition titles, which reflect the fashions, and the concerns of the time, the teachers' interests and what they wanted their girls to concentrate their minds on.

The love French Jews felt for France, their patriotism are expressed in one of the most prominent theme in the exercise books, when together with their fellow Frenchmen, they lament the loss of Alsace and Lorraine to Germany in 1871. In Alsace especially, the anger and sorrow caused by the annexation of Alsace to Germany caused France to become the lost 'promised land', a loss never to be accepted. French patriotism is expressed in a choice of texts such as LA MARSEILLAISE and MARCHE LORRAINE extolling the glory of France and the willingness to defend her and die for her. Also strongly represented are the undying attachment and the historical loyalty of the inhabitants of Alsace and Lorraine to France, their traditional hatred of all things German, their immense frustration at being obliged to live under German rule and their defiant attitude towards Germany and the Germans.

One of the poems UN BAPTEME ALSACIEN (A christening in Alsace) describes the feelings of the parents of a newborn girl. Aren't the arrogant Germans going to claim her as German as soon as she is born? It is their right after all. Reeling under the affront, the father registers the child with the German authority. Asked what name he wishes to give the child, he replies, suddenly inspired; I will give her a name that is filled with hope. Write it down, Prussian, her name is France.

In another poem LA LECON DE GEOGRAPHIE (The geography lesson), a German teacher is giving a geography lesson in a school in Strasbourg. Her mission is to turn children nurtured to love France and to hate Germany into enthusiastic Germans. With a triumphant look on her face, she points out the border between Germany and France on the map, stressing the fact that Alsace is inside the German border. She orders the children to show Strasbourg, Colmar and Mulhouse on the map. Show me Metz? she snaps. Then, with a sarcastic smile, she asks one child; And now, show me where is France? The child answers In my heart, Miss!

LE PARI (The wager), a piece of prose, illustrates the contempt in which the Germans were held and the determination to defend the honour of France. Some time after the 1870 war, Prussian generals who had been in command during the war assemble in Berlin for a banquet. One of them who had married a Parisian woman insisted that she accompanies him to the banquet. As the dessert was being served, a toast was proposed, To Berlin, the intellectual capital of the world! Unable to contain herself, the Parisienne raised her glass and said, To Paris, forever capital of the world. This gave rise to a lively discussion on the respective merits of Berlin and Paris that ended indecisively, without anyone being able to score a final point. The young woman then proposed a wager. She would have anything one would care to give her transformed into an objet d'art that could only emanate from Paris. The wager was accepted and the following morning a very short white hair was delivered to the young woman. She set off for Paris but all the jewellers she consulted refused to take on the challenge apart from one apprentice who thought he had an idea that might work. A few days later, back in Berlin, the happy Parisienne presented the generals with a Prussian eagle holding in its beak a hair with a medallion at each of its ends, one representing Alsace and the other Lorraine with the inscription; You are only holding us by a hair.

The condition of women is another recurring theme; women who are true to the conventions of the time and women who rebel against them, women as national heroines, women as mothers, young women and their romantic dreams, ambitious, cunning, protesting women thirsting for freedom and independence, using their wit and cunning to outsmart any plot that would have them comply with preconceived ideas about their role in society. Historical figures such as Marie Stuart and Jeanne d'Arc epitomize, in lyrical terms, the cherished feelings of undying love and loyalty for France. The ordinary women of Alsace show their allegiance to France by outwitting the German occupants and resisting actively or passively their persistent attempts to Germanize their beloved Alsace. Women in the traditional tragic role of the self sacrificing mother in her maternal love, women having to beg to feed their children, women as the selfless soul of the home, women as devoted war-time nurses, tending the wounded irrespective of nationality, are to be found in a number of passages.

Probably as a reminder that some women have to work or wish to work for money and perhaps drawing attention to their own position, the teachers also selected texts with images of women as paid workers. They are described as hardworking, efficient, modest, loved by everyone. Financial independence earned by one's own labour is what a girl must aim for! In CONSEILS A MA FILLE (Advice to my daughter) F. G. Condorcet advises his daughter to make sure that she is able to earn a living so that she will not have to rely on other people for money. In any of her undertakings, a girl must be orderly, clean, diligent, kind and honest. Above all, she must not be lazy. Stories based on the conflicting emotional needs of young girls dreams of love and the social and often financial necessity of finding a suitable husband to satisfy the expectations of parents and society are to be found again and again. In POURQUOI (Why), a poem by J. Mesnil, a young lady of marriageable age, full of romantic ideas, wants to know why love and good looks are not enough to find a suitable husband. Why does she need a dowry? Why is society so full of people who are friendly to your face but tear you apart as soon as your back is turned? Why, O Why?

LE SOULIER ROSE (The pink shoe) by Jacques Normand, speaks of a subterfuge used to discourage an unwanted rich pretender chosen by well meaning parents for their daughter. She deliberately loses a shoe under the table and pretends to be afflicted with a limp. The young man does not want her any more; she is saved.

Other passages tell of young girls objecting strongly to the way they are treated in comparison with the way boys are treated. Girls always have to be good, shy, knit stockings, while boys are allowed to climb trees and follow their inclinations. Whatever we girls do is wrong; let's not be silent any more. We shall be called troublemakers, but who cares? I came to preach the young girls crusade. Enough of this” it is not for young girls” which stops us from reading certain books, from dressing according to our own taste in fashion, from saying No, from going out when and where we like, alone, without a chaperon, even when it is raining. I want to go and tell M.Ps (senateurs et deputes); stop wasting your time, voting on unimportant things and look at the problems young women have to face. From CE N'EST PAS POUR LES JEUNES FILLES (Not for young ladies).

Ambitious women, foolish enough to submit wholeheartedly to the dictates of fashion and to the demands of high and mighty dressmakers in Couture Houses, are ridiculed in LA COUTURIERE (The dressmaker), a prose passage. Thinking the election of her husband as an MP imminent, a woman prepares for her new role. The wife of a depute (Member of Parliament) must have a dress to fit the occasion, that is the rule. It goes without say that only the very best of Couture Houses will be capable of producing such a unique garment. In the expensively decorated salon of the Couture House, where she is kept waiting for two hours, the future Mme Depute begins to worry about the cost. After having been assessed by the sales person in charge and a further half hour wait, the director of the establishment condescends to see her and declares :

- Yes, of course.

- Madame is wrong; today's fashion is for flat women and a woman who eats could swell up and cause our darts to pucker.

- Oh well, I shall stop eating, that's all.

- Does Madame have relatives?

- Yes, a lot.

- Relatives interfere and we alone have the necessary expertise to advise our clients.

- Well, I shall end all communication with my relatives forthwith.

Exposing the hidden motives of those who dispense and those who accept charity, the meanness of would be do-gooders was another favourite subject. In FINE POINTURE (A tight fit) by C. Porieux, a do-gooder vents her anger at the ingratitude of today's beggars. She who would have given her last shirt to help the less fortunate, is beside herself when her 'gifts' are not appreciated. After all, isn't an old torn shirt of hers better than no shirt? When after being given such a shirt, the mother of a poor family comments that it will do as a floor cloth, she is outraged. When a blind man to whom she had given an old crust of bread when he had asked for a little money tells her that she has given charity to his dog who unlike his master still has teeth, she is beside herself. Begging women who use children to soften peoples 'hearts, beggar children cunningly taking advantage of people are to be found alongside misers who refuse charity even to the most deserving.

There are only three texts with a Jewish theme. Two are centred on women. They illustrate the evil of organised anti-Semitism and the heroic behaviour of two Jewish women. The third paints a vivid image of how stupidity and misinterpretation of one's own religion can lead to a tit for tat situation that does nothing to improve understanding between Jew and Christian.

POURQUOI CELEBRE-T-ON CHEZ LES ISRAELITES LA FETE DE POURIM? RACONTEZ L'HISTOIRE D'ESTHER (Why do Jews celebrate the festival of Purim? Tell the story of Esther) is given as an essay title. As this title is given to Jewish pupils in a Jewish institution, the use of Jews rather than we, as in why do we celebrate... is, if somewhat surprising, in keeping with the spirit of the time.

The second text LA JUIVE (The Jewess) by H. Greville recounts the desperate attempts of a Jewish woman, a widowed mother, to save the life of her eight-year-old son during the Spanish Inquisition. She hides from her child the fact that they are Jews, she celebrates the Sabbath in secret, and she does not eat pork. At the same time they pretend to be Christians. Finding her Christianity unconvincing, the inquisitors arrest her and condemned her to be burnt at the stake. In a supreme attempt to save her child she says that he is not Jewish and that he is not her child, her own child having died. The child is saved. In the bottom of his heart he senses the truth. He never becomes a Christian.

In the third text, a poem by Guichard called LE JUIF ET LE CHRETIEN (The Jew and the Christian) we are told that a Jew has fallen into a well. A Christian who happens to be there runs to get a ladder but the Jew refuses to use it because it is the Sabbath. The following morning the Jew asks for the ladder to be brought back but the Christian refuses, for today is Sunday and my religion is as important to me as yours is to you.

Men are always represented from a feminine perspective either as hard working, stern breadwinners in a family context or as potential lovers or husbands. In one or two instances they are soldiers sent away to fight for their country, perhaps wounded in the process, but always seen through the eyes of the women back home.

Some pages are devoted to extolling the merits of a virtuous conduct; love of hard work and strict discipline or to describing the beauty and grandeur of nature, to allegories in which animals take on a human role.

Whenever Germans are present in a text, it is exclusively in the negative perspective of the detested occupants.

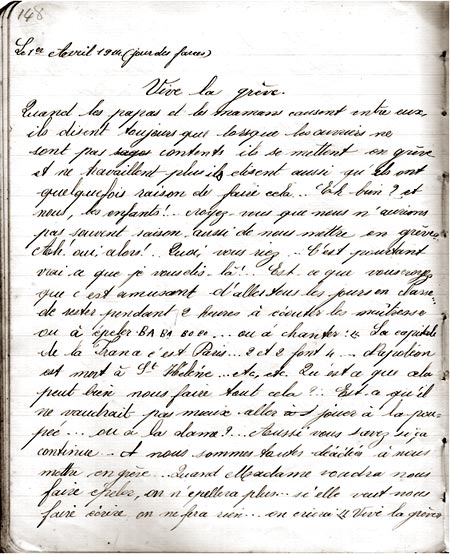

A number of compositions allow us to participate in some of the events in the life of the students at the Institution de Mmes Aron et Weil. The 1st of April was a special day. Students were allowed a certain amount of licence of expression. Pieces of writing dated 1st of April have, as a subtitle, Jour de Farces (a day for tricks and jokes). MENU DU PENSIONNAT ARON ET WElL, in a mixture of French and Yiddish, lists such items as Poulets gerupft au refectoire (chicken plucked in the refectory). Langue du 'Chasen Mons.Klein' (the tongue of Mr.Klein, the cantor). Salade pisse au lit (salad pee in bed). Pisse au lit is a play on pissenlit (dandelion). Biscuits montes au dortoir' (biscuits raised in the dormitory) a play on montes ,also meaning taken up to. Fruits aux vers (wormy fruit or fruit with verse). Dessert, quand il vient vous Ie verrez (dessert, you shall see it when it appears).

Another passage dated 1st of April 1914 called VIVE LA GREVE (Long live the strike) lists students’ complaints about school and teachers and how they might emulate workers in factories and go on strike. If parents find it possible to understand the grievances of factory workers and support their going on strike, they must surely approve when their own children want to go on strike! No more classes, no more teachers, no more mothers, no more fathers, no more piano lessons, no more dressmakers. FREEDOM! There is though a danger of becoming an ignoramus, uncouth and dirty, so that no one will want to know you. We shall discuss it further before we decide on strike action!

LA FETE DU JOUR DE L'AN (New Year's Day) is the subject of another composition. Lucy is a little homesick and she writes that it is the first time she is spending New Year's Day away from home but she soon cheers up when she is told of the special programme for the day. Mme la Directrice is allowing the girls to see the New Year in at midnight and to lie in bed till 8 o'clock the following morning. As they get up, the girls declare their New Year resolutions. At 10a.m. they are taken to town in groups, each group with a teacher and after lunch to the theatre to see Manon, an opera by Massenet. Cette belle journee etait trop vite passee (this wonderful day passed too quickly) is how Lucy ends her composition.

Lucy's exercise books represent the work done in French classes. The rarity of titles with a Jewish interest and the lack of copied or dictated texts from Jewish authors can at best be understood by taking into account the history of French Jews and their self image as Israelites Francais. There is no mention in the exercise books of the way special days in the Jewish calendar such as the festivals and the Sabbath might have been celebrated at the Pensionnat, though it goes without say that they would be observed. A photograph from 1904/5 shows the girls in fancy dress for the festival of Purim (Feast of Esther).

Some girls at the Institution came from a fairly orthodox background though the vast majority came from homes with a middle of the road, unquestioning observance of Judaism. Kosher food, the observance of the Sabbath and the Festivals, synagogue attendance at least on some occasions were so much part of life that they were probably taken for granted and were just a normal continuation of what the girls had experienced at home. It wasn't new and exciting like the town of Nancy with its Place Stanislas, its Bergamottes and its theatre, French poetry and literature, feminism, making new friends, being part of a world so different from anything one had experienced so far. We can assume that there were exercise books for other subjects with possibly one of them devoted to Jewish studies, though they did not become part of Lucy’s cherished reminiscences.

Even the recent Dreyfus case and budding political Zionism do not seem to have made any impact but Lucy and other former pupils would, until ripe old age, remember and recite with glee poems such as JEANNE AU PAIN SEC (Jeanne on bread and water) by V. Hugo.

Other aspects of life at the pensionnat are revealed in Lucy's compositions. There were two long breaks in the school day, one from 10.00 – 11.15am. and another from 4.00 – 5.00 pm. The girls were given a snack and then allowed to go out in the garden to chat and play games, whatever the season of the year. Oh que les recreations sont courtes et les heures de classes si longues! (How short the breaks and how long the classes!) concludes Lucy. Teacher's comments; c'est la conclusion d'une jeune fille paresseuse (a lazy girl's conclusion).

The students slept in dormitories and ate their main meals in a refectory. Most of the pieces of work in the exercise books are dated and as there are no gaps in the dates, we must assume that the girls didn't go home for holidays except in the summer, at the end of the school year.

From the teachers' remarks at the end of dictées and compositions we can see that the teachers addressed the girls as vous and not the more familiar tu, as befitted young ladies in a French finishing school. From personal testimonies we know that discipline was strict at the pensionnat. The girls could only go out accompanied by an approved person. Lucy had to be collected and brought back when she visited distant relatives who lived in Nancy. The rabbi or the cantor of the Nancy synagogue came to teach Judaism and the students were taken to synagogue services. Lucy could read her prayers in Hebrew. Only kosher food was served. Grace after meals (benshen, birkat ha-mazon) was said after each main meal. Friday afternoon was spent cleaning and polishing desks. Hairbrushes had to be washed in a mixture of water and ammonia to discourage head lice.

Time spent at the Institution de Mmes Aron et Weil, in Nancy was a happy time, fondly remembered for the rest of one's life. Long lasting friendships were formed. Lucy and her best friend Jeanne never lost touch with one another, in spite of two world wars, until Jeanne's death. While in Nancy, they had decided that they would marry brothers so that they would never be parted.

The Institution offered a varied programme of studies; liberal studies, French, elocution, deportment or how to walk gracefully with the tips of your bottines (short laced boots) turned inwards, how to curtsey and make a knicks (small curtsey), embroidery, shorthand, art, English and music. Some of the courses were optional. Examinations in French set by the Alliance Française could be taken. Successful candidates were awarded a Diplome de Langue Française (Certificate in French Language). With sufficiently high marks, a State Certificat d'Etudes Primaires (Certificate in Primary Education) could be obtained. Prizes were given to exceptional pupils in subjects such as painting, with a Gallevase as first prize.

There were two Jewish boarding schools for girls in Nancy; that of Mmes Aron et Weil and the Pensionnat de Mmes Braun-Kahn, rue de Strasbourg. The opening and closing dates of these institutions are not available but it is thought that the Pensionnat Aron et Weil closed just before the Second World War.

Some of the speeches made by Mme la Directrice of the Pensionnat Braun-Kahn on prize-giving day remain. In her speech of the 6th Aug.1890, Mme la Directrice tells her students of their good fortune at being presented with books, not ordinary books, but handsomely bound books as prizes, for the first time in the history of the Pensionnat. She stresses how vital it is to own books, how pleasurable it is to read them and she warns against the damage reading bad books can do. She ends wishing her students a happy holiday and reminding them of the importance of being always pleasant and helpful to everyone and not to forget everything they have learnt. The printed copy of the speech is followed by a list of achievements in the various examinations attempted by the students. The 1892 speech analyses true and false politeness and civility and their consequences. A young lady who is not polite is but an ill-bred girl is Madame la Directrice's verdict.

(My dear children, in France, to be polite is a law to be applied in all situations, however modest they may be. ...To be uncivil always denotes a lack of education, a fault of character or stupid pride).

In 1893, Madame la Directrice begins with congratulations for six students who did particularly well in examinations. She then launches into a long diatribe in praise of a well-ordered life, a place for everything and everything in its place. Added at the end of the speech, again a summary of examination passes. In all three speeches, all quotations and examples are from secular sources; none are taken from Jewish writers.

At the Institution de Mmes Aron et Weil, the principal was Mme Aron. She managed the boarding school with the help of her daughter Mademoiselle Weil, known to the girls as Mademoiselle Alice. Her duties included some of the teaching. All the teachers were female and Jewish.

Mme Aron was keen to recruit students and it was possible to discuss terms and barter. A father who is considering sending his daughter to the Institution writes in a letter to Mme Aron, on the 12.9.1903.

Girls came to Nancy mainly from Alsace and Lorraine; a few were from Germany. Most of them were away from home for the first time; for many it was the first opportunity to hear French spoken correctly and without an accent all day, every day. Lucy was luckier than most. Her mother's family had always been fiercely French. Before she was married, Lucy's mother had spent some time in Avignon, keeping house for her brother Jules who was the rabbi of the town. This gave her the opportunity to improve her already very good French. She also had three sisters, Josephine, Regine and Eugenie who lived in Paris with their respective husbands. Lucy was very fond of her Parisian aunts. At home, one spoke some French, but a combination of Western Yiddish -Judeo-Alsacien- and the dialect of Alsace was more commonly used. Early pieces of work in Lucy's exercise books show the typical difficulty speakers of these languages have to distinguish a T from a D and a P from a B. Some sentences written in French, supposedly, are word for word translations from these languages. They make little sense in French and have to be read with these languages in mind.

Jewish parents who could afford it, chose to send their daughter to Jewish boarding schools perhaps to follow a fashionable trend but also to benefit from intensive courses in French, to complete their education and to show their loyalty to France. The social standing it gave was certainly not negligible. A well-bred, well-educated young lady, finished in Nancy, had her chances of finding a suitable husband greatly enhanced. Parents of lesser means kept their daughters at home, embroidering their trousseau of table linen, bed linen, vests and nightshirts, huge knickers and petticoats while they waited for a husband. Wealthy parents had their daughters’ trousseau lavishly embroidered by nuns in convents. Girls from poor families often went a l'interieur (inside France) as opposed to Alsace-Lorraine, to work as maids with wealthy Jewish families, or as shop assistants.

The vast majority of young ladies at the Institution de Mmes Aron et Weil in Nancy hailed from rural Alsace, from small towns and villages such as Osthouse, where Lucy was born in 1899. Her father was a cattle dealer, a popular occupation amongst Jews and a very lucrative one, though it demanded very hard physical work as well as a thorough understanding of the mentality of the local farmers. She had a brother called Robert, older by one year. They both attended the village school where, to the dismay of the Jews and many others, the language of teaching had been German since 1871 and would remain so until 1918. When Robert and Lucy reached the normal school leaving age of 14, Robert was sent as a day boy to the Catholic Institut St Joseph, a boarding school for boys, in Matzenheim, a neighbouring village. The Institut made special provisions for Jewish boys and Robert cycled there and back, every day. Lucy was sent en pension (as a boarder) at the Institution Aron et Weil, in Nancy. There she experienced, probably for the first time, living in an entirely French environment. The impending war brought her back to Osthouse in the Summer of 1914.

A typical village of that particular region of Alsace, set amongst fields of beet, maize, barley, wheat, oats and tobacco plants, Osthouse was and remains a farming community. Records of a Jewish presence in the village go back to the last quarter of the 17th century. Alsace emerged generally depleted and battered from the 30 Year War in 1648. The population of Osthouse had been reduced to 20-30 families. The village belonged to M. de Bulach, a member of the lower nobility. A small chateau belonging to the family still stands in Osthouse today although M. de Bulach's descendants do not reside there any longer. In order to repopulate his village, M.de Bulach encouraged people of all sorts to come and live there. He authorized Jewish families to settle in the village against payment of a settlement fee, followed by an annual protection tax. This ensured a regular income for M. de Bulach.

Jews brought with them their community spirit and their business skills. Many were poor or even destitute but determined hard work and parsimony brought prosperity for at least some of them and for the village. They dealt in cattle, hop, grain, property, leather and skins; they sold groceries and cloth at markets and door to door, visiting surrounding villages and farms. LE TERRIEN DE 1683 (Land Register of 1683), quoted by Antoine Kipp in LA COMMUNAUTE ISRAELITE A OSTHOUSE (The Jewish community in Osthouse), unpublished, shows that in 1683 only one house in the village was owned by a Jew named Isaac Heilbrunn. Its description corresponds to the property, with two houses on each side of the pathway, where a first synagogue was erected in the beginning of the 18th century. Having become too small for the growing Jewish population, it was replaced by a new larger synagogue in 1865. Destroyed by the German occupants in 1942/43 it is now a mere ruin. A cantor/minister led the prayers in the synagogue and was in charge of the religious education of the children.

In the years 1685-1731, five houses are recorded as having been purchased by Jews. By 1784, Osthouse had 450 inhabitants, namely 387 Catholics and 63 Jews representing 14 Jewish families. There was only one widower. All the other families consisted of husband and wife, mostly with children. Some had a married child, perhaps son and daughter-in-law, living with them. One family is recorded as having a Jewish living-in maid. Most men and boys had biblical or well known names, the women and girls mostly Yiddish names. In July 1808, an imperial decree made it compulsory for Jews to adopt a surname. Many who already had a surname kept it or occasionally chose a new first name; others seized this opportunity to change surname and first name and adopted more French sounding names. This is how Levi Hefe became Levi Eve, Ebstein Morle became Ebstein Marieanne and Wolff Leibel acquired the name Blum Leopold.

By 1807/08, records vary slightly as to the number of Jews in the village. For 1807, we find 618 Catholics, 30 Calvinists and 86 Jews (11.7% of the population). In 1808, there are 107 Jews for a total population of 750 souls. 1851 saw the largest number of Jews living in Osthouse, 132 individuals. According to the minutes of a City Council meeting of the neighbouring town of Erstein, dated 3rd Nov, 1864, a proposal was discussed to establish une ecole communale israelite (a Jewish state school) in Osthouse for the Jewish children of Erstein and Osthouse. This bears witness to the importance of the Jewish presence in Osthouse. The proposal was turned down on the grounds that the Jewish chidren of Erstein had access to the local non-Jewish state school without even having to pay a fee! The first Jewish school for girls in Strasbourg, financed by voluntary contributions, had opened its doors in 1844. By the beginning of the 20th century, a number of small towns such as Bischheim, Ingwiller, Brumath, Obernai, with large Jewish communities, had a Jewish school.

Until the advent of the First Republic, Jews were not allowed to reside in certain towns. They were allowed access during the day and against payment of a tax they could conduct their business activities. They were not allowed to spend the night in the towns. They had to return to their villages when, as was the case in Erstein, the church bells struck 10pm. By 1850 a Jewish community had established itself in Erstein. Jews owned shops; they opened joinery and upholstery workshops. The first synagogue was built in 1882 and in 1904 the town's council gave the Jews a piece of land to be used as a cemetery. In 1920, the Jewish community of Erstein had 160 members, several kosher butchers and a Jewish innkeeper.

Gradually, Jewish families left Osthouse, lured away by the better business, social and educational facilities offered by the neighbouring towns of Selestat, Erstein and Strasbourg with their larger Jewish population.

By 1910, only 43 Jews remained in Osthouse; by 1936 all the Jews left the village. Following the trend, Lucy's parents sold their house in the Rue des Pierres, in Osthouse and bought the altogether more substantial two storey house at No 5, Rue de l'Eglise, in Erstein. They moved in, with their son and daughter on the 15th of April 1920. Lucy was then 21 and of marriageable age. Living in Erstein would enhance her chances of making a suitable match. She was used to a comfortable but not pampered life. In the house in Erstein she was given a first floor front bedroom. It had been newly decorated and furnished with new acajou (mahogany) furniture. Lucy loved her new room. Later in life she still fondly referred to it as ma chambre de jeune fille (the room I had before I was married). Food had always been plentiful. Her father invariably brought home fresh produce from the farms, vegetables and fruit according to the seasons. In spring there would be fleshy white asparagus gathered early the same morning, later summer fruit and autumn fruit. Pikes and carps from the rivers and ponds were brought in on Thursdays, to allow for them to be prepared for the Sabbath. Meat was bought from the kosher butchers. Lucy's clothes were chosen carefully to enhance her auburn hair, her fair complexion and her green/yellow eyes. She travelled to Paris to visit her aunts. She had a dowry and a beautiful trousseau. She was an accomplished young lady. Her spiritual needs had not been ignored. She was given a prayer book PRIERES D'UN COEUR ISRAELITE (Prayers of a Jewish Heart), containing prayers and meditations for most circumstances. It had a special section with prayers for married women. The book was then in its 10th edition. It was written in French with a few transliterations from the Hebrew or Aramaic. For Lucy, it remained a book for private prayers, a book in which she would eventually write dates she wanted to remember, the hour and date of her parents’ death according to the Jewish and the ordinary calendars, birthdays, the dates and venues of her daughters’ weddings, the hour and date of the birth of her grandchildren, etc. When Lucy attended synagogue services she could use the standard prayer book and pray in Hebrew with the rest of the congregation.

Entrevues (occasions especially set up for a young man and woman to meet) were organized, as was the custom. Lucy had her own standards and one pretender was turned down because he addressed her by her first name as soon as they had met and suggested they might as well say tu to each other from the start. There were others she didn't like and no doubt some who did not like her. Then one day, Mme Metzger, next door, sprang into action. She had a relative who was also related to a young man in Switzerland who had just lost his mother and wanted to get married. As Lucy was not averse to the idea of a meeting, Charles journeyed to Erstein, accompanied by his and Mme Metzger's relative. First impressions must have been good. They met again and became engaged. Lucy and Charles were married at the Synagogue in Belfort, on the 13th August 1923. The resident Rabbi of the Belfort Synagogue conducted the service together with Rabbi Jules Bauer, Lucy's uncle who addressed the bride and groom. He reminded them of the high standards set by both families in their every day life and in their observance of Judaism. He explained the duties of a Jewish husband and of a Jewish wife. The secret of true happiness in marriage is that you should have but one soul and one heart, that you should love each other, that you should never forget the teachings of our faith. The Almighty will then answer your prayers and grant you a life of happiness.

Lucy and Charles made their home in Switzerland and lived there their entire life. They had two daughters. Lucy and Charles now lie buried in the Jewish cemetery of Basle (Switzerland). Lucy was my mother and Charles was my father.

- Allocutions de la directrice du pensionnat de Mme Braun-Kahn, Nancy, à l'occasion de la distribution des prix en 1890, 1892, 1893, non publiées.

- Aron, Arnaud. Prières d'un Cœur Israélite. Paris, Durlacher.

- Badinter, Robert. Libres et égaux; l'émancipation des Juifs (1789-1791), Paris, Fayard, 1989.

- Berman, Léon. Histoire des Juifs de France, Paris, Lipschutz, 1937.

- Bloch, Joseph. Historique de la Communauté juive de Haguenau, Haguenau, Imprimerie du Bas-Rhin, 1968.

- Blumenkranz, Bernhard. Histoire des Juifs en France, Toulouse, Privat, 1972.

- Caron, Vicki. Between France and Germany; the Jews of Alsace Lorraine, 1871-1918, Californie (É.-U), Stanford University Press, 1988.

- Feuerwerker, David. L'Émancipation des Juifs en France, Paris, Albin Michel, 1976.

- Hyman, Paula. De Dreyfus à Vichy. L'Évolution de la Communauté juive en France, 1906-1939, Fayard, Paris, 1985.

- Hyman, Paula. The Emancipation of the Jews of Alsace, New Haven et London, Yale University Press, 1991.

- Job, Françoise. Les Juifs de Nancy, Nancy, Presse Universitaire de Nancy, 1992.

- Katz, Pierre. La communauté juive d'Osthouse, non publié.

- Kipp, Antoine. La communauté israélite à Osthouse, non publié.

- Leuilliot, Paul. L'Alsace au début du XIXe siècle, tome III. Religions et culture, Paris, S.E.V.P.E.N. 1960.

- Malinovich, Nadia. French and Jewish. Culture and the politics of identity in early Twentieth-Century France, Oxford, The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2008.

- Martin, Erwin. Inventaire des archives contemporaines et administratives de la ville de Strasbourg : 1789-1960, Strasbourg, Mairie de Strasbourg, 1961.

- Metzger, Robert. La communauté israélite d'Erstein, non publié.

- Minutes de la réunion du Conseil municipal d'Erstein du 7 mai 1864

- Neher-Bernheim, Renée. Histoire juive de la Renaissance à nos jours, Paris, Klincksiek, 1973.

- Prost, Antoine. Histoire de l'Enseignement en France 1800-1967, Paris, Armand Colin, 1968.

- Raphaël, Freddy (éd.). Saisons d'Alsace, revue trimestrielle, 20e année, n° 55-56, Paris, Istra.

- Raphaël, Freddy et Robert Weyl. Juifs en Alsace, Toulouse, Privat, 1977.

- Raphaël, Freddy et Robert Weyl. Regards Nouveaux sur les Juifs d'Alsace, Paris, Istra, 1980.

- Salomon, Lucy. Trois cahiers d'exercices rédigés pendant l'année scolaire 1913-1914, Nancy, non publiés. Plusieurs lettres, témoignages et photographies non publiés.

- Scheid, Élie. Histoire des Juifs d'Alsace, Paris, Durlacher, 1887.

- Schwartzfuchs, Simon. Du Juif à l'Israélite, Paris, Fayard, 1989.

- Schwartzfuchs, Simon. Napoleon, the Jews and the Sanhedrin, Londres, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1979.

- Treschan, Victor. Struggle for Integration: Jewish Community of Strasbourg 1818-1850, Wisconsin (É.-U), University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1978.

- Vigée, Claude. Un Panier de houblon, Paris, J-C. Lattes, 1994.

|